THE MACCHIAIOLI

THE MACCHIAIOLI

A brief but truthful story of an artistic innovation

by

Elisabetta Matteucci

If the history of art boasts cases of isolated geniuses like Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Caravaggio, Ingres, Van Gogh, Picasso, each of them committed to promote a real progress, the modern times show that the great achievements, as it very often happens also in the scientific field, are fruits of group work. Not even painting can escape this reality; let us only think of tendencies like Divisionism, Cubism, or Futurism whose importance was so great that they contributed to define the style of the twentieth century. The Macchiaioli represent the confirmation of it, as they are the first example of a group of independent spirits who produced a real revolution in art, thanks to a technique that radically changed the traditional concept of academic aesthetics.

As about the origin of the term, there are no precise documents; unlike “Impressionism”, coined with reference to Monet’s painting Impression, soleil levant, displayed in 1874 at the first exhibition of the Parisian movement, the attribute “Macchiaioli” appears for the first time in 1862 on the “Nuova Europa”, a conservative journal with a Catholic orientation. An anonymous commentator used it with a derogative intention as regards the exhibition of the “Società Promotrice Fiorentina” of that year. Mocking the style of a group of young painters who were present at the display, the journalist said, “They are young artists who got it into their head to reform art starting from the principle that the effect is everything“. This statement hints in a few words at the innovative significance of their technique. In the sixteenth century “fare alla macchia” meant to trace quickly and in short a theme, which corresponded to the rough sketch the artist had in mind. By giving up the academic practice in drawing, the Macchiaioli manage to interpret the motif with a simple synthesis, by distributing patches of colour -“macchie“- directly on the base (canvas or panels), thus achieving with an incisive chromatic effect powerful and really original chiaroscuro contrasts.

An exceptional example of a Macchiaioli painting at the dawn of it is offered by Antonio Puccinelli, from Castelfranco (1822-1897); finding himself in Rome for the artistic institution, in 1852 he paints La passeggiata al Muro Torto (figure 1, private collection). A work carried out with a synthetic execution which, for its precocity, is unanimously considered an incunabulum of the new Macchiaioli technique; a sort of combination between the style of the Tuscan movement and the view of the modern Parisian society that Impressionism will offer ten years later.

fig.1

However, who are the Macchiaioli? The group is made of twelve young men from different social classes; they were born between 1820 and 1835 and were inspired by patriotic feelings. Giuseppe Abbati (1836-1868), Cristiano Banti (1824-1904), Odoardo Borrani (1833-1905), Vincenzo Cabianca (1827-1902), Adriano Cecioni (1836-1886), Giovanni Costa known as Nino (1826-1903), Vito d’Ancona (1825-1884), Serafino de Tivoli (1826-1892), Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908), Silvestro Lega (1826-1895), Raffaello Sernesi (1838-1866), Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901). Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931), Giuseppe de Nittis (1846-1884) and Federico Zandomeneghi (1841-1917) must be added to the former because of the fellowship established in Tuscany with the members of the group between 1866 and 1873. What they have in common is the idea of subverting the old academic rules that suffocated the artist’s creativity.

Although not all of them were Tuscan, why did Florence become the centre of their adventure? For the young people who made the Grand tour, that is to say the educational and cultural journey, the mid-nineteenth-century Florence represented the” Little Athens in Italy”, the favourite destination of numerous foreigner communities that considered it their second home country. In 1850, it has 50,000 inhabitants and prestigious museums and libraries; therefore, it is planned on a human scale and is at the same time a cosmopolitan city. At five minutes’ gig ride from the centre, you can enjoy unique landscape scenery (fig.2), which had already been a source of inspiration for the greatest personalities of the Renaissance.

fig.2. Panoramic view of Florence, 1860. Department of Prints and Drawings of Uffizi

Pietro Giordani who, in his correspondence with Leopardi, called the city “the Garden of Eden” gives the confirmation of the ideal climate you can breathe there, thanks also to the policy in favour of arts pursued by an enlightened sovereign like Peter Leopold of Lorraine. Such a harmonious atmosphere is favoured by the ideal convergence of political and cultural factors. Florence is the home country of Giovan Pietro Viesseux, Gino Capponi and the “Antologia”; a prestigious centre for liberal spirits and the progressive-minded artists who took part in the Revolutions of 1848, like Domenico Induno and Eleuterio Pagliano from Milan, Francesco Saverio Altamura from Apulia and Domenico Morelli from Naples.

fig.3. Old aged Gino Capponi (Meozzi photo, Florence)

The dates of the Macchiaioli movement cover a period of time of twenty years: from 1855, which was thought to be the year of its birth, to the beginnings of 1870, when this technique will exhaust its function of being the new concept of pictorial synthesis, owing to the break-up of the group due to personal happenings and disagreements arisen among them. However, before then, a handful of enthusiastic young men had started hacking in the Sienese countryside, near Staggia, painting what “reality” offered to their sight. Nearly all of them attended the school of Andrea Markò from Hungary (1826-1895), who was famous in Florence for its Flemish-style landscapes. Among the pupils, intolerant of working shut up in the studio, Serafino de Tivoli, a very lively young man belonging to a Jewish family from Leghorn, stood out from the rest. It will be him to sign the first paintings not inspired by imagination, but by what nature showed to him. By playing a leading role, he will encourage his friends to follow him in his visits to Villa San Donato, where the Russian prince Anatolio Demidoff (fig.4), Matilde Bonaparte’s husband, had gathered one of the most important modern art collections in Europe, made up of works bought on international markets or directly from famous artists like Ingres, Delacroix, Corot, Decamps, Delaroche, Meissonier. Visiting that collection represents a valuable opportunity for the Macchiaioli to have a first contact with the modern figurative French culture.

fig. 4. Anatolio Demidoff.

We cannot speak about the Macchiaioli without mentioning the place where the group came into being: “Caffè Michelangiolo”. Inside this café, considered the centre of their ideas, the battle for establishing new aesthetics will arouse an echo destined to be acknowledged all over Italy and not only. Its seat is in “Via Larga” (the present “Via Cavour”) and in 1856, it becomes a meeting point for men of letters and intellectuals followers of Mazzini. In a short time, it will become so famous that any artists or personalities passing through Florence will be eager to visit it.

A leading and charismatic figure among the Macchiaioli is Diego Martelli (1839-1896), the only nineteenth-century Italian critic who Roberto Longhi defined of European stature and who had the merit for being the first to catch the importance of Impressionism, by spreading its ideas in Italy, in a memorable conference held in 1879 at the “Circolo Filologico” in Leghorn. A liberal spirit, Fattori, Abbati and Lega’s close friend, Martelli belongs to the well-off Tuscan bourgeoisie of the post-unity period whose education was inspired by the thought of some intellectuals like Pietro Giordani, Raffaele Lambruschini, Gino Capponi and Gian Pietro Viesseux. After his study at Cicognini boarding school in Prato, his idealistic, restless and outgoing nature puts him in contact with the circle of people who frequented “Caffè Michelangiolo”. He goes there for the first time in 1856 accompanied by the history painter Annibale Gatti (1827-1909) and there he finds a passionate and lively atmosphere aroused by the news about the Universal Exhibition in Paris, reported by de Tivoli. Courbet, after being refused by the jury, has set up, in open controversy, the “Pavillon du Réalisme”, a sort of exhibition of his own works, inspired by a non-conformist view, alternative to the official one of the “Palais de l’Industrie”. For the first time the Macchiaioli hear de Tivoli speak about the “ton gris”, the new pictorial technique tried by Gabriel Decamps and Paul Delaroche, consisting in painting nature by observing it through a dark mirror to filter the chiaroscuro contrasts better. Also Domenico Morelli (1823-1901), brother-in-law of the man of letters Pasquale Villari, gets to the “Caffè” taking with him the fame achieved thanks to the canvas showed at the Bourbon Exhibition, Gli Iconoclasti: first evidence of the interpretation of a historical-romantic painting carried out with large areas of colour, fruit of free spontaneity. The presence of the Neapolitan painter at the “Caffè” will influence the development of the Macchiaioli painting, first through the application of it to the sketch of the historical painting, then to the from life painting.

Cristiano Banti, La morte di Lorenzino de’ Medici (fig. 5, private collection): example of a first stage of the Macchiaioli painting, the most radical one in which the colour is mere substance applied without a drawing, so that the subject appears outlined in chromatic masses. This is a sketch of the famous painting La congiura, inspired by the finding of the body of Lorenzino, a controversial figure in the Medici’s family who was killed in Venice on 26th February 1548.

fig. 5 (studio)

Giuseppe Ciaranfi (1838-1902), Bambini sul greto del fiume (fig. 6, private collection): in this case the Macchiaioli technique is applied to the interpretation of subjects taken from everyday life. What is significant is the fact that an academic artist, traditionally respectful of the convention, tried this new procedure.

fig. 6

As every revolution worthy of the name, also the Macchiaioli one has its great opportunity to attract the public. This happens in September 1861, on the occasion of the important National Exhibition of Fine Arts set up at “Parco delle Cascine” in Florence to celebrate the Unity of Italy. This is an event of national importance which attracts painters and exponents of the most advanced current trends to the capital of Tuscany; an event which gives the young of “Caffè Michelangiolo” the opportunity of meeting the best known personalities. The academic exponents’ reaction towards groundbreaking works like Cabianca’s Le monachine (fig. 7, private collection), Signorini’s Pascoli a Castiglioncello and Borrani’s 26 aprile, will also get the commentator of “Nuova Italia” to coin the term Macchiaioli with denigrating intent.

The Macchiaioli become prominent figures of an aesthetic renewal that affects the thematic aspects besides the technical ones.

Painting in the open air, in search of motifs and effects that express good manual skills and emotions before nature, becomes a characteristic of each exponent.

fig. 7

fig. 8

Giovanni Fattori, Soldati francesi (fig. 8, private collection). Fattori is one of the first to try from life painting when, in June 1859, he portrays a squad of the French troops in the retinue of general Lamoricière, sent to Italy by prince Gerolamo Bonaparte and camped at “Pratone delle Cascine” in Florence. The Leghorn painter studies the lines and uniforms of the soldiers in the sunlight and fixes the impression of the scene on a small panel, apparently ordinary in its morphology but extremely complex and original in its structure.

This happens when in Florence the taste for the late romantic-academic painting still prevails and the first landscapes inspired by Corot have just appeared, through the echoes of the “plein air” painting of the “Ecole de Barbizon”, which have reached “Caffè Michelangiolo”. The new concept of reality that Fattori and the “Michelangiolo” group are offering is something extraordinary, absolutely and disruptively modern. The painter is especially inspired by the military world which he documents, not in the stereotyped celebratory and epic form used by David or Delacroix, but with a more humane and benevolent point of view which perceives in the soldier a defenceless figure, whose life depends on the succession of events beyond his control. The small dimensions of the supports serve to focus, in the foreground, the subject, as if the eye highlighted the details through a magnifying lens. The use of surfaces made out of mahogany boxes of cigars is an aesthetic as well as a practical choice: the grain and the basic colour of these small boards painted with a quick and immediate stroke produce effects that are harmoniously consistent with the pictorial rendering.

Fattori’s first studies at “Parco delle Cascine” are followed, between 1858 and 1860, by the ones Cabianca, Banti and Signorini carried out in La Spezia and Portovenere. Just during that season, the experimental phase of the Macchiaioli painting ends. From then onwards, the focus of interest becomes the attempt to make it more incisive through the lightning effect, a vital element of the painting. The variables thus achieved, seen inside intimate and quiet places, along with a patriotic spirit will originate a more realistic representation.

fig. 9

Odoardo Borrani’s Il 26 Aprile 1859 (fig. 9, private collection) summarizes in itself the feeling of popular participation to the feverish tensions leading up to the expulsion from the city of the Grand Duke of Lorraine. The painting was identified in 1970, year of its finding, thanks to the testimony handed down by Adriano Cecioni in his friend’s profile: “Il 26 Aprile 1859 in Firenze is represented by a girl who is sewing the Italian tricolour with some rags. A very difficult attempt to resolve the dark spot represented by the figure inside the window with the sunshine outside. Borrani solved the problem very well; his painting gained the public’s favour and was immediately bought by a member of the royal family.”

The person was the Prince of Carignano, a well-known patron who, visiting the exhibitions of the time, gathers an important collection of Macchiaioli painting. An oral tradition has it that in the painting the artist ideally portrayed the marchioness Matilde Bartolommei, wife of Ferdinando Bartolommei, a leading figure of the Tuscan Risorgimento.

The kind of light will also evolve and, two years later, Borrani himself will paint Cucitrici di camice rosse, a direct derivation of 26 Aprile, where the brightness of the luminous contrast turns out to be toned down in a quieter hue, which favours a more intimist representation of reality. A domestic interpretation of the events which marked Garibaldi’s defeat at Aspromonte in August 1862, in which Borrani recreates the climate of the rising Tuscan bourgeoisie after the Unity, burning with patriotic ardour and firm in its feelings. Some elements emerge – the window, the furniture and the sense of tranquillity – that reveal a sensitivity to the biedermeier culture, got into Northern Italy with the Austrian domination; Florence itself is ruled by the Lorraine family until 1859.

Diego Martelli in a photo with dedication to his friend Serafino de Tivoli. Viareggio, Matteucci Institute, Vitali’s fund.

In 1861 Martelli (fig. 10), linked to the group since his adolescence, inherits, on the death of his father, a large estate that extends from the coast of Castiglioncello to Nibbiaia. Driven by enthusiasm, he starts an ambitious activity of agricultural reconversion, by improving vast uncultivated areas to increase the wood and wheat production. In the summer of the same year, he invites there his closest friends from “Caffè Michelangiolo”, certain that the contact with such uncontaminated nature would favour their inspiration. Being their stays there very frequent (1861-1865), the farm becomes the centre of a lively artistic coterie. This is the beginning of what will become the Castiglioncello School, in which each of those young men will direct their research towards a lyric transposition of the landscape. Abbati, Sernesi, Borrani (fig. 11-13), and Fattori will pay the most frequent visits, in five years.

fig. 11, Giuseppe Abbati, Lido con buoi al pascolo (private collection)

fig. 12, Raffaello Sernesi, Castiglioncello dalla punta del Bocca (private collection)

fig.13, Odoardo Borrani, Carro rosso a Castiglioncello (private collection)

The horizontal development of the motif is a common feature to the works carried out in that part of the coast, in which nature is the protagonist, so as to highlight its vastness through the use of long and narrow supports, in order to obtain a better spatial rendering. In those views, the human presence has a minor role; whereas a leading role is played by the light variations, the vivid tonalities typical of the place, the silent atmosphere tinged with a vein of sadness, due to the artist’s thoughtful premonition that shortly afterwards such an Eden-like site will change forever.

Not all the Macchioli will take an active part in the Castiglioncello coterie; owing to their bashful nature, some of them prefer to draw their inspiration from everyday life-style whose ideal setting is the home and the family background.

The contemporaneous Piagentina School is, instead, full of warmth and a silent, quiet atmosphere. The main idea of its paintings is given by the rhythms of a life spent in the country houses, where time passes slowly, marked by the farm work, the household activities and the noble leisure.

A locality outside the ancient Florence curtain walls, near the torrent Affrico, called Pergentina or Piagentina is the scenery of this new kind of representation, in which the study of the female psychology is the painter’s main interest. The reason why this place becomes a habitual destination is Lega and Borrani’s decision to live there, even though in different periods.

Silvestro Lega, Una veduta in Piagentina (fig. 14, private collection)

The cottage Batelli is the background of two masterpieces of that happy season: Una visita and Il pergolato. Lega, who, together with his friend Borrani, will be the leading personality of the Piagentina School, painted them at the end of the Sixties. He starts to go to that country place at the beginning of the decade, after getting involved with Virginia Batelli, the Florentine printer Spirito Batelli’s daughter. Following the break-up of her marriage, the woman had got back to live with her father and her sister Adolfina. For Lega, so introvert and not very inclined to have social relationships, the contact with that family, a real microcosm of feelings, represents a situation full of warmth, which was ideal for his inspiration. Whereas Borrani will move to Piagentina soon after his marriage with a midwife, Carlotta Meini, who will soon become his real muse.

fig. 15. Odoardo Borrani, Ritratto di bambino in piedi (private collection)

fig.16. Silvestro Lega, Il Pergolato. Un dopopranzo. (studio)

Private collection

Silvestro Lega, Il pergolato: in the Twenties the painting (fig. 16), whose original title is Un dopopranzo, was in Viareggio, in Emanuele Rosselli’s house, together with other valuable Macchiaioli works like Signorini’s Marinai a riposo, Fattori’s Le acquaiole and Borrani’s Raccolta del grano a Castiglioncello, recently recovered.

When the Florentine collector decides to put it on the market, the association “Amici di Brera” raises a subscription that will favour its destination to the Milanese picture gallery.

During the period spent in Piagentina, Lega reached the height of his stylistic path. In the light of the new face Florence is taking, thanks both to its forthcoming role of capital, and to Giuseppe Poggi’s future projects for the city enlargement, the painter’s attention turns to the fourteenth and fifteenth century Tuscan painting, to Piero della Francesca. In Il canto di uno stornello (Florence, Modern Art Gallery in Palazzo Pitti), the iconografic reference to the altar piece of the Renaissance, of Italian and Flemish type, is evident in the strong upward motion characterising the life-size portrait of the three Batelli sisters. The most reliable hypothesis for such an uncommon and complex choice is that Lega himself, inside the cottage Batelli, considered the fact that the painting should be looked at from bottom up, and so put just on the wall halfway the staircase leading to the next floors. The upside-down perspective, even though undoubtedly unusual, could support this theory.

On the occasion of the monographic display set up in 1988 in Milan and in Florence, the piece of the score in the picture was played and used as background music for the exhibition.

As regards the critics’ attitude towards the Macchiaioli, everybody knows that some of them tended to establish an unequal confrontation with the Impressionists, considering them inferior. Nowadays, it is already a common opinion that the protagonists of the Tuscan movement are the expression of a culturally different social situation.

What they have in common is, instead, the fact that they have always been unappreciated and mocked by the Institutions and have tenaciously fought to achieve just a bit of glory during their life. As for the Macchiaioli , in 1867, Martelli promotes and finances the “Gazzettino delle Arti del Disegno” that, according to the programme he drew up with other learned friends like Maurizio Angeli, should be the official organ of the group’s ideas, thus beginning a new style of art criticism. He was flanked by Signorini whose literary qualities and intuitions are revealed in a series of articles that, together with the ones written by Martelli himself, represent the first basic contributions to the Tuscan movement. Unfortunately, the lack of a determinate programme, of wise economic management and the controversy risen on each publication, cause the closure of the magazine after only half a year from its birth. A defeat deeply felt by Martelli and the group which is to be added to the grief at the premature deaths of Sernesi, passed away in 1866 during the war against the Austrians, and of Abbati who, in 1868, dies because of the hydrophobia caught by his dog.

These events were felt by the Macchiaioli as signs of a great adventure arrived at the end. Most of them are left with the problem of providing for their everyday necessities. As for the market, the luckiest ones can only rely on the clients turning up at the annual exhibitions of the “Società Promotrice” and on the ones they receive in their studio. Therefore, in comparison with the Impressionists, they are disadvantaged by the lack of support from enterprising art dealers like Durand-Ruel, or from collectors like Paul Gachet, Van Gogh’s doctor, Ernest Hoschedé, or Victor Chocquet who, though an ordinary custom officer, gathers one of the most extraordinary collections of modern French painting, thus becoming a strong supporter of Cézanne’s work. Also for this reason some figures that joined the Tuscan unit, like Boldini, de Nittis, Zandomeneghi, consider Paris a capital that can fulfil their expectations. Two years before, in 1866, d’Ancona and de Tivoli had already chosen to move there. When Boldini, de Nittis and then Zandomeneghi follow them, the cutting of the umbilical cord will be so definite that it will coincide with a new stylistic identity, connected with the Impressionist influence. In this regard, Martelli’s role is fundamental, since he established a bridge between the researches of the Florentine and the Parisian groups. He went to Paris for the first time in November 1862, and again in 1869, 1870 and in 1878. The last stay will be the most useful for the connections he established with the artistic and literary elite met at the “Café de la Nouvelle Athènes” and in Giuseppe and Leontine de Nittis’s salon. He will establish a solid friendship with Degas who he repeatedly met in the studio of Zandomeneghi, who will give him hospitality in 1878 on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition; the Italian writer’s two portraits made by Degas (Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland) and by Federico Zandomeneghi (Florence, Modern Art Gallery of Palazzo Pitti) are evidence of their relationship.

In the Seventies, the situation of the Florentine group greatly changed; the spirit of association weakens remarkably also owing to the success of the new currents of Naturalism. Only the most gifted personalities like Fattori, Lega and Signorini will be able to keep up with the realistic language. Each, with their own temperament, will be able to create an independent and original expressive style, in line with the most up-to-date European tendencies.

Silvestro Lega, Eleonora Tommasi che cuce in giardino, 1883 ca. (fig. 17, private collection)

Come già avvenuto con i Batelli a Piagentina, nel decennio Ottanta Lega si unisce al gruppo familiare dei Tommasi a Bellariva, località a sud As already happened with the Batelli family in Piagentina, in the Eighties, Lega joins the Tommasi family in Bellariva, a locality south of Florence. Following the trend of the family portrayal, he will prefer a light and intensely bright colour range, characterized by a delicate and quick stroke that “hints”, as Martelli writes, “at the Impressionist’s serene gaiety”.

Giovanni Fattori, La morte del cavallo – E ora? (fig. 18, private collection)

Fattori will remain coherent with his passion for rural themes, but adding to them a socio-humanitarian tone that, for some aspects, anticipates Viani’s twentieth-century Expressionism. In fact, it is not just a coincidence that the latter, encouraged in his first studies, by the elderly master, re-uses the theme of the Morte del cavallo, though in a less naturalistic way.

Signorini is different, a real globetrotting artist, he will link his activity to the several places he discovered in the last few years: the Cinque Terre, the Isle of Elba, Piancastagnaio at the foot of Mount Amiata and Chioggia.

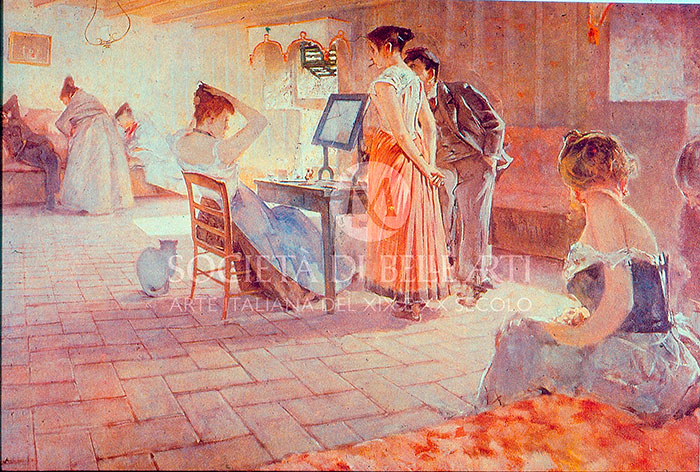

The typical and picturesque scenery of those lands, filtered through the European experiences, will connote his style making it similar to an Impressionist painter’s and thus becoming a refined interpreter of landscapes. Also the Florentine artist will show an interest in social themes whose backdrop is represented by environments and situations in which the human condition appears, sometimes, in its most dramatic aspects. With this viewpoint, in 1898, he paints one of his masterpieces: La toilette del mattino.

In the centre of the scene, set in a brothel in Lontanmorti Street in Florence, where the artist probably used to go, you can see a group of girls with some “clients”. Signorini, sure that a subject like this, worthy of Zola’s pen, would scandalise the conformists, for a long time keeps the canvas turned backwards in his studio in Santa Croce Square. Only in 1930, by decision of the heirs, it will be put on the Milanese market and bought by Arturo Toscanini, whose family will keep it until after his death in the yellow lounge of Durini Street, where his piano was located. When he recalled the purchase of the work at a high price, criticised by his wife Carla de Martini, the Maestro said,” That light from the half-closed green shutters, the woman combing her hair before the mirror, the friend yawning on the sofa…. Why should I do without such a painting? Never again. My passions are three: paintings, of course the ones I like, Leopardi’s letters, Mozart’s letters…”. Wally Toscanini, the Maestro’s daughter, will remember that, during the shootings of Senso, Luchino Visconti very often went to study the painting from which he took his cue for the famous scene where the countess Livia Serpieri, interpreted by Alida Valli, visits the barracks of the Austrian corps in Venice to meet her lover, the lieutenant Franz Mahler.

The strong artistic temperament of Lega, Fattori and Signorini will have a remarkable influence over the new generation of Tuscan painters who, moulded at the Macchiaioli’s side, will stand out at the exhibitions held between the Seventies and the Eighties. Francesco and Luigi Gioli, Eugenio Cecconi, Niccolò Cannicci and Nomellini, jointly with others, will promote a new type of representation that, though respecting the Tuscan tradition of drawing, will tend to synthesize the detail, giving the subject, often taken from the rural world, an allusive meaning, which leads one to reflect. However, their story is another chapter of modern painting, whose narration is worth telling another time…